Making 'Board Game'

- Jun 30, 2016

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2025

In 2016, it was the 30th anniversary of my 16mm short film Board Game – shot in 1984, finished in 1985, premiered on BBC TV in November 1986.

Seized by melancholy, I dug through my old file boxes of notes and letters devoted to that film. Along with my terribly-drawn storyboards, my rejection letter from the National Film and Television School and my prize money receipt from the BBC, I found an old article that I wrote for Movie Maker magazine, sometime in January 1987.

The amateur filmmaking magazine’s editor, Tony Rose, had covered the BBC competition. As well as some nice compliments about Board Game, and a barbed note chastising the NFTS for rejecting me, Mr. Rose mentioned that he had been intrigued by how we had brought the chess pieces to life in my short film — it was not by Harryhausen-style stop-motion animation, as many people suspected. So I responded by sending him a 900-word explanation, detailing the work of my talented effects man, Nigel Booth.

Movie Maker did not publish my tell-all account, as they claimed I did not have imagery to support such a lengthy piece. But I was amused to see, years later, that I was apparently shooting for the moon by considering another outlet for my article, as indicated by a single-word scribbled on the top of my manuscript: ‘Cinefex?’

I can’t recall if I ever sent Cinefex my story – sorry, Don and Jody, if I did – but I thought it would be fun to finally confess how we brought those chess pieces to life.

Read on, for secrets about the making of Board Game....

The Chess Men of ‘Board Game’

Article by Joe Fordham (January 1987)

Chess set by Nigel Booth

The idea for the film was simple. Two strangers facing each other in a quiet game of chess find themselves so involved, emotionally, that things get out of hand.

A ‘Bored Boy’ (Richard Merry) sees his stiff-necked opponent, ‘Lazy Eye’ (Simon Mendes), pick off his pieces, constantly outwitting any openings he can make in the game. As Bored Boy’s paranoia and hysteria mount, the chess pieces begin to react with him, snarling and grimacing, trembling and screaming. Finally, the film reaches its own conclusions.

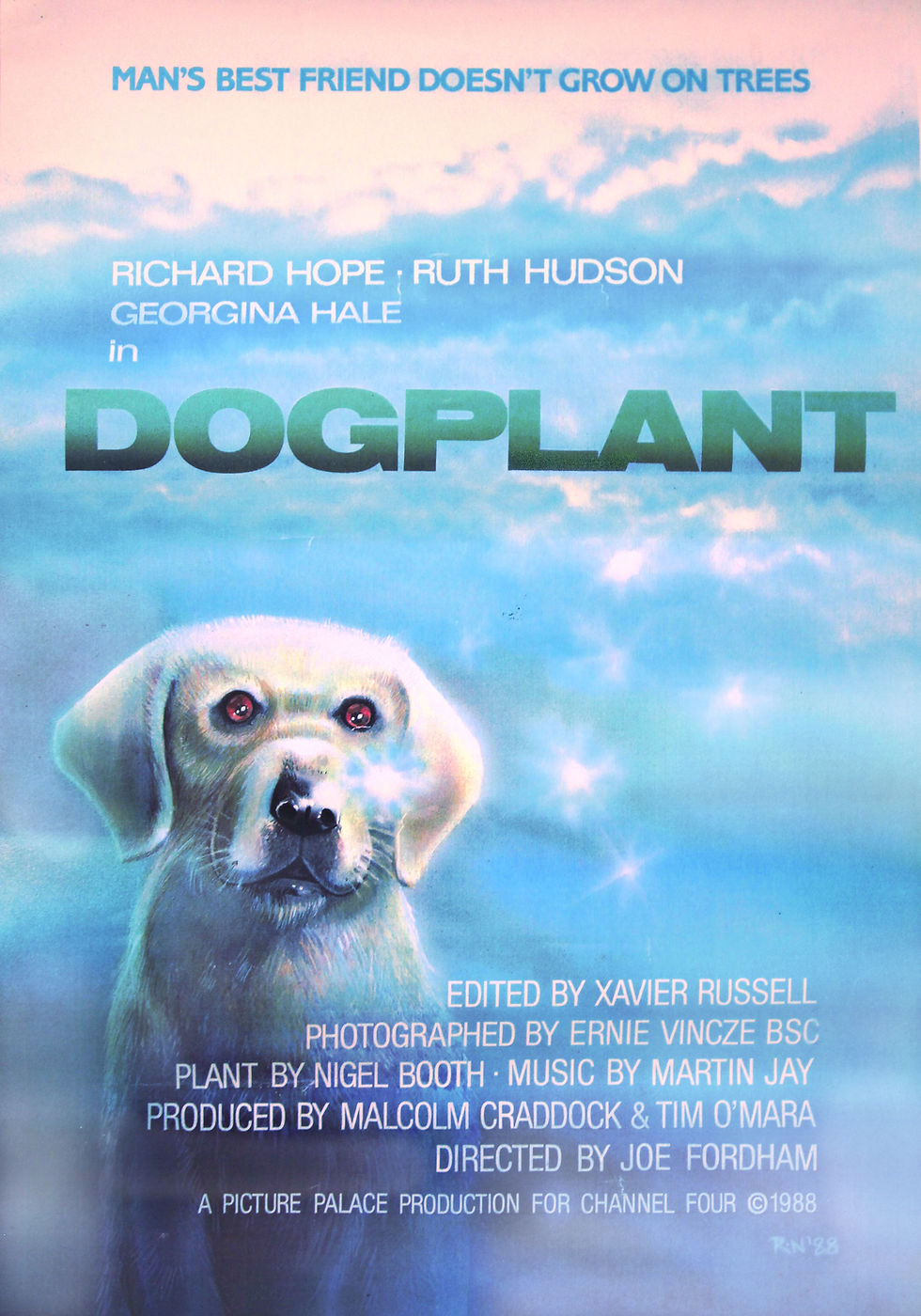

To create this emotional chess set, we called upon the talents of a member of our filmmaking group, ‘Dangerous Visions,’ who has been making nasty things for our earlier Super 8 productions. Nigel Booth – who is now working in the film industry in the creature effects trade – designed and sculpted the entire cast of King, Queen, Knight, Bishop, Rook and Pawns. This gave us maximum control over the two most important criteria: the characters of the figures, and the ability to bring them to life.

Nigel took inspiration for his chess figures from a blend of ancient Nordic carvings, Alice in Wonderland Tenniel designs, and members of his family. We decided against our idea of a rabid knight, but produced a detailed woeful King, a bilious Bishop, a sexy Queen and an imposing supporting cast of rooks and pawns.

To create the main chess set, Nigel sculpted and cast 32 figures in dental casting stone. He made the ancient homemade chessboard to look appropriately stained and aged, and as an extra vintage touch backed the board with 1950s newspapers. After the main body of shooting, Nigel then began several months of sculpting, casting and moulding. While I edited the film on nights and weekends, using equipment borrowed from the postproduction company where I worked in London, Nigel was also working when he could between finishing his first professional job, sweeping up and helping out in the creature shop on Highlander. We were both putting what we were learning at work into practice on Board Game.

What we were trying to do was, in principle, what they did on Gremlins or E.T.: animatronics. This is a technique that allows you to create moving, living objects in a real-life situation, in real time. Although stop-motion has its own merits, we wanted to very quickly get across little bursts of emotions with our characters, so we decided to use animatronics, preferring its ‘real time’ look.

Nigel could not fit the mechanics necessary inside a character only a few inches tall, so he re-sculpted his own designs, scaling them up. This was made easier since he was using his own original sculpture to begin with, as was part of his plan. He took castings from molds of his sculptures and made soft foam latex skins and rigid resin substructures.

He then fitted each skin over the substructure skull, and attached it to the internal mechanisms that would provide internal movement. A series of strings threaded up through the skull and attached to the inner surface of the foam skin. After a skillful paint job, the character would then be ready for what was, basically, marionette puppetry. For the first time, we were able to see these apparently solid ceramic objects moving and, with sound effects, coming to life.

I made a forced perspective, scaled-up section of the playing surface, like something out of Lewis Carroll, with foreground squares large enough to accommodate the oversize characters, diminishing to background squares sized to their smaller counterparts. Nigel then mounted the puppet characters through the board and controlled their movements by pulling on their cables, threaded through the table. It took a certain amount of rehearsal (and an on-the-set paint job to transform the White Queen to the Black Queen) but we were able to complete filming in my parents’ garage in one afternoon.

Finally, I could slot the remaining shots into place in the cutting copy of my film. Now all I had to do was the sound effects track, the music, the sound mix, the neg-cut and the answer print. We premiered the film on August 2nd, 1985, at the Bijou cinema in Wardour Street, and in November 1986 it won £2,000 in the BBC TV Showreel ‘86 film competition.

The story of the chessmen of Board Game proved to be a microcosm of the making of the film. It took months longer than we’d hoped, or Nigel had expected. Baking the foam stank out Nigel’s parents’ house, and caked his father’s garage floor in latex and plaster. And I discovered I have a strange allergy to foam latex that makes my face swell up like a werewolf transformation. The fruit of all our work is on screen for only a very short time.

But all that work, and the short screen time, is necessary for special effects. Creaky though the saying ‘less is more’ may seem, it is true that a filmmaker should only need to produce a special effect, the impression of images, rather than gloating over it. We didn’t exactly have the money to produce much to gloat over, but from the reactions we have had to Board Game it has struck me how this observation is so true. Nigel’s chessmen may only be on screen for a few seconds, but they leave you with a lasting and magical impression.

Click to play:

Comments